The current bull market turned eight years old this past month. This makes it the second longest bull market in post WWII history. Rather than celebrating the length of the current recovery, most commentators treated the milestone like a funeral. Widespread sentiment is that the market is near a peak.

The conventional wisdom is that valuations are too high, and that rising interest rates will hurt profit margins. With uncertain future revenue growth and concerns about valuations, the case to get out of stocks seems airtight. Upon closer inspection, it seems that this pessimistic outlook depends on some questionable assumptions about market cycles.

Stock market drawdowns result from a crisis of investor confidence

Bear markets generally (but not always) coincide with an economic recession. More importantly, they reflect a loss of investor confidence. The magnitude of the decline reflects the severity of the crisis of investor confidence. Investors describe a market decline of more than ten percent as a correction. A bear market means that prices are down at least twenty percent from their highs.

Biggest declines occur after an extended period of rising confidence

Market cycles follow a predictable pattern. A bull market emerges at the maximum point of pessimism. Once all the optimists surrender, confidence has nowhere to go but up. The bull market climbs a wall of worry, and eventually people become a little less gloomy, until finally confidence starts to pick up. After several years, this confidence evolves into irrational exuberance. These markets are most susceptible to a severe sell-off.

The belief that stocks are due for a bear market rests on the assumption that confidence has been steadily improving over the last eight years, and investors are now over-confident. This is a strangely nostalgic view of the last eight years.

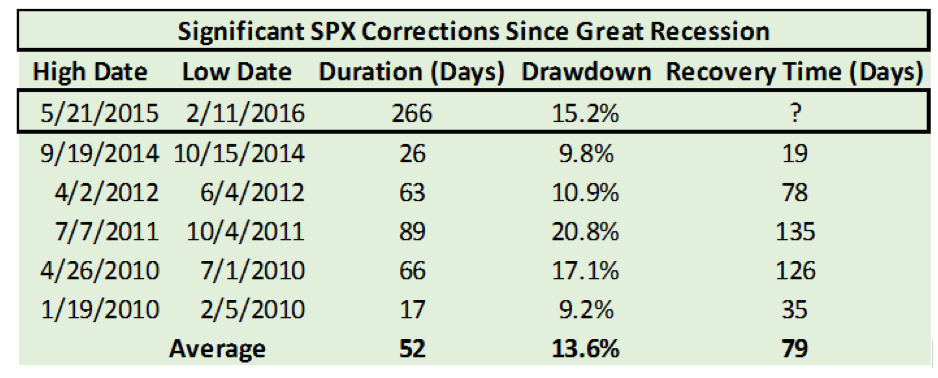

Investors have suffered through several crises of confidence over the last eight years

The stock market has endured several crises of confidence over the last eight years. The 20.8% sell-off in 2011 that resulted from the downgrade of U.S. debt felt very much like a market earthquake at the time. In 2010, investors stressed about a collapse in the Greek economy and the potential end of the European Union. I don’t remember any analysts arguing that the pain wasn’t real because the market only fell more than 20% on an intraday basis (if the market ended the day down more than 20% it would have been widely described as a bear market). Just because these shocks didn’t technically qualify as a bear market doesn’t mean that investor confidence wasn’t seriously shaken.

The global economy is in the initial stages of economic recovery

The market is constantly discounting bad news as it occurs. The idea that a sell-off becomes more likely as the length of time since the last bear market increases assumes that there is a certain predictable timeframe to the market cycle. Yet, no one seems able to predict these economic earthquakes in advance. Every cycle is different and occurs under different conditions. Like physics, a market in motion will continue in that direction until counterforces overwhelm the market’s momentum. There is no conceivable way of knowing when this will occur.

The global economy is just now recovering from a slow-down in economic growth. This slowdown was a result of a collapse in energy and commodity prices. From June 2015 through February 2016 the global stock market suffered a bear market drop of 24.5%. International stocks are still well below the levels of 2015. If the U.S. economy slows and the rest of the world continues to pick up the pace of economic growth, the U.S. will be handing off the baton of economic leadership.

Crises of confidence are random, yet constant. We don’t know the severity of the earthquake until it’s over. Only with the benefit of hindsight can we identify whether a market decline was so severe as to call it a bear market. The fact that large U.S. stocks haven’t gone down by more than 20% in the past eight years should be the last thing we worry about.

Asset allocation provides buffer to market turbulence

Every Barden Capital client has a portfolio that is structured to your unique objectives. We won’t invest in stocks with the resources that you expect to use within the next five years. This gives you time to recover from the most severe investment earthquakes.

Long-term returns are more predictable—short term returns are fairly random

The 2011 debt crisis was essentially a bear market. The S&P 500 fell to 1,119 from over 1,300. Now, less than six years later, the S&P 500 is over 2,300, which is 80% higher than it was prior to the debt default meltdown. The unfortunate investors who put their entire nest eggs into the market just before the debt downgrade have still achieved an annual return of more than 10%–assuming they stayed invested. Time heals all wounds.

That’s not to suggest that all global stock markets have the same expected return. U.S. stock valuations are the highest in the world. The dollar is at a fifteen-year high relative to our trading partners. The energy and commodities-based economic downturn was most severe outside of the United States.

International markets will most likely outperform the U.S. over the next five to ten years

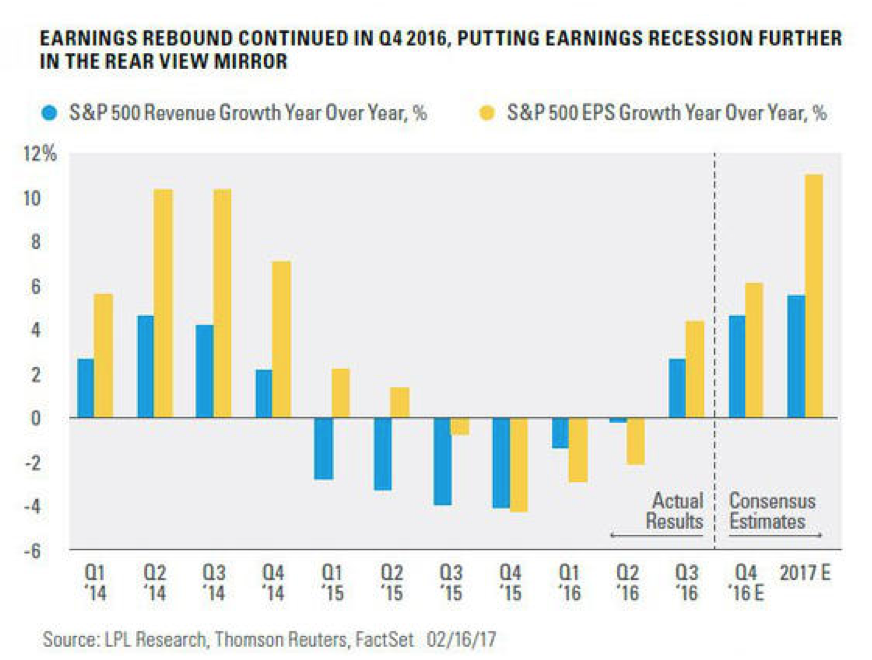

Now that energy and commodity prices are more stable, commodity dependent economies are beginning to recover. Companies across the globe are once again seeing revenue growth, which will support stronger earnings throughout 2017. The economies that are most dependent on commodities and energy should benefit the most from the global economic recovery.

According to JP Morgan, the expected seven percent revenue growth this quarter is similar to early-cycle growth. After enduring a revenue decline in 2015 and early 2016, analysts expect revenue to grow substantially this year, taking earnings up as well. Even if the U.S. is due for a slow-down, there is substantial untapped growth potential around the world today.