Summer Melodramas

There have been two suspense stories unfolding in the markets this summer. We have been building up to these cliffhangers for a few years. The Federal Reserve is on the verge of raising interest rates for the first time in almost a decade. In Europe, Greece is forcing the wealthier European nations to decide whether it’s worth the cost to keep Greece in the Eurozone.

While the market media expounds breathlessly about the implications of these events, investors seem almost indifferent. We are now almost half way through the year and the U.S. stock market has stayed in a narrow range–not rising or falling more than three percent from where it began the year. Most forecasters expected substantial market volatility this year, but the markets are currently about as exciting as watching grass grow.

Greece

Investors are correctly looking past the resolution of these dramas. The size of the Greek economy is only about two percent of the Eurozone Economy. The market recognized that mutual self-interest would force a compromise between the wealthier northern European countries and heavily indebted Greece. Now that Greece has secured a three-year lifeline, the Greek drama will move off of center stage for the time being.

It’s not the size of the Greek bailout that concerns the Eurozone. The greater concern is the precedent it sets for the larger debtor nations, Italy and Spain. Presumably, the bailout process has been sufficiently painful for Greece that it will serve to discourage any other European debtor nations from following in Greece’s footsteps.

The long-term impact of the Greek debt crisis is that it forces the European countries to have a “relationship defining talk.” Are they going to end up as something like the United States of Europe? And all be able to agree on centralized fiscal and foreign policy? Or are they going to preserve their independence on all things other than monetary policy? It’s not clear that there’s a consensus on this crucial question. Right now, European nations are more engaged than married. It’s taken fifty years for them to get to this point. Investors shouldn’t expect Greece to be the last hurdle to defining the ultimate nature of the Eurozone, but a year or two without another “emergency” summit of European finance ministers doesn’t seem like to much to ask.

Federal Reserve and the Economy

At the beginning of the year, the consensus of economists was that the Federal Reserve would raise interest rates by one-half of one percent. With an intermission in the Greek drama, odds are about 80% that the Federal Reserve will raise rates in September. The bond market reflects the increasing probability of higher interest rates. Long term government bonds have depreciated about four percent in value this year. Corporate bonds are down about three percent.

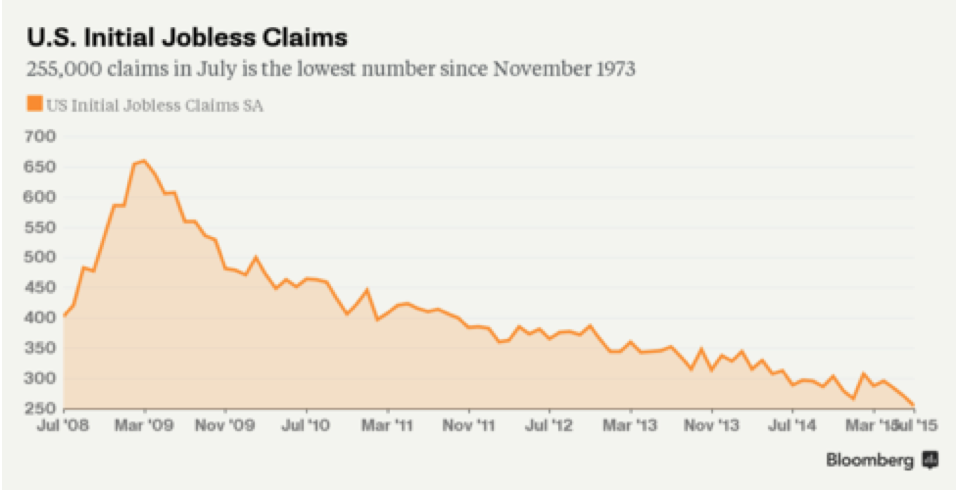

There is no doubt that the economy continues to recover. Jobless claims fell to their lowest level in forty years last month. This suggests that people who are searching for work are finding work. The unemployment rate is probably the best single indicator of the current economic environment.

Investors should not fear the first interest rate increase. Historically, it’s coincided with very good returns for stocks. On average, stocks have increased thirty-three percent over the two years following the first increase in interest rates. Increasing interest rates are a sign of economic strength and reflect an economy that has fully emerged from the previous recession. We likely have a couple of productive years for stocks before we face a substantial risk of a recession. A downturn becomes more likely only after seven or eight interest rate hikes, which no one foresees in the near future.

Market Outlook

In spite of what appears to be market stability, underneath the surface there is substantial turbulence. The sectors of the stock market that prospered in 2014 were bond substitutes like utilities, real estate, and energy limited partnerships, while the more aggressive growth sectors of the market lagged. Now that bonds are no longer appreciating in price, the sectors of the stock market that most highly correlate with the bond market are also suffering. The Dow Jones Utilities index is down almost 8 percent in 2015, while the growth oriented NASDAQ is up more than six percent.

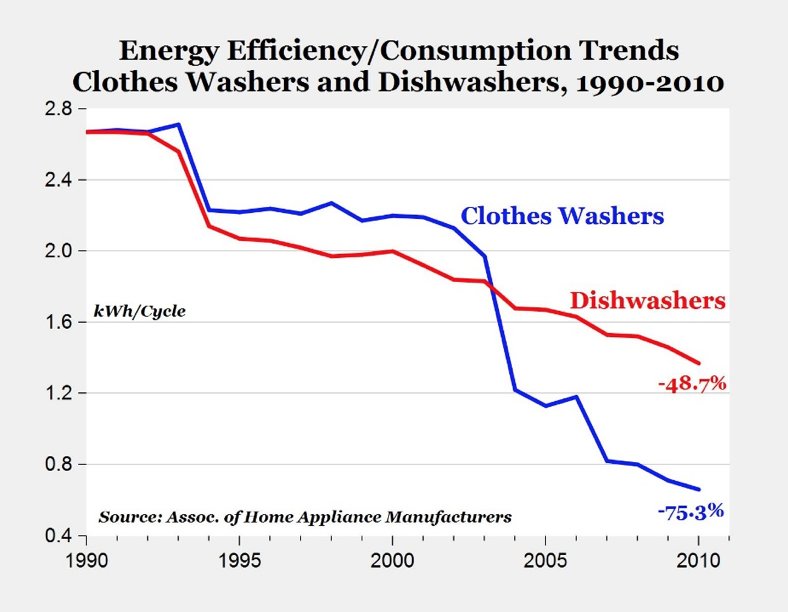

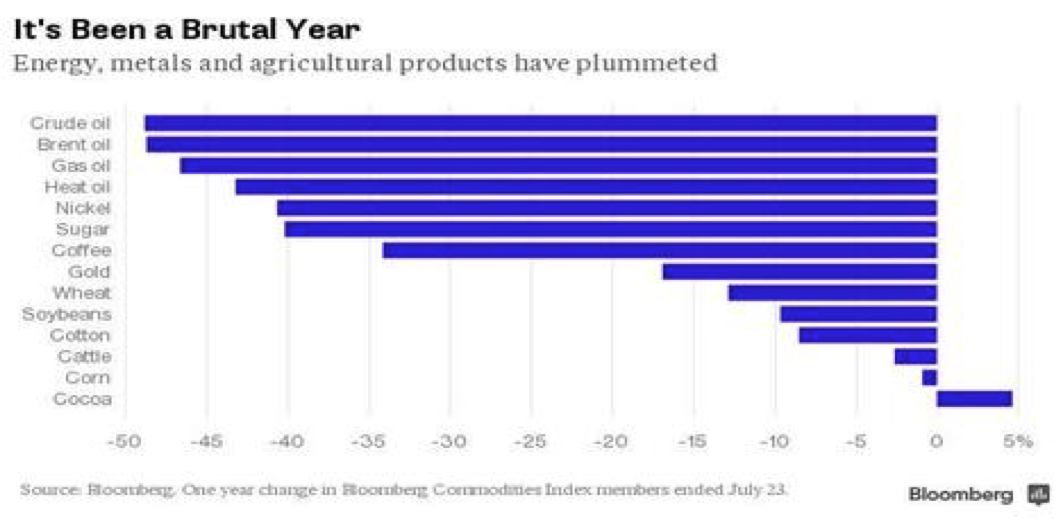

In spite of the generally improving global economy, commodities and energy prices have collapsed over the past year. The combination of increasing supply with decreasing demand causes a fall in the price of any commodity. Oil and natural gas is increasingly abundant. Southern Iraq is producing oil again after the long process of rebuilding their oil industry following the war. Innovations in extraction allow the U.S. to produce much more than what was previously thought possible, and OPEC decided against cutting production. Now, it appears that Iran may begin to increase their oil exports. This coincides with a drop in demand around the world. China is shifting away from commodities intensive investment in its infrastructure, and energy efficiency standards are allowing us to run the same appliances but with much less energy consumption. Today’s clothes washers use one fourth of the energy of appliances sold in 1990.

For the vast majority of consumers around the world, this is a savings windfall, but this windfall comes at the expense of commodity and energy producing companies and countries. In 1980, the combined weighting of the U.S. stock market in basic materials and energy was 40%. Today, it is only 11%. The economy is much less sensitive to mining and energy. Historically, a similar drop in energy and commodities would surely lead to a recession. Currently, that recession is limited to industries in the energy industrial complex.

The collapse in earnings expectations for this sector of the economy is a major factor in the current market stagnation. Energy sector stock prices are down more than 20% over the last year. The good news is that as the energy sector shrinks, so does the economy’s overall sensitivity to it. Energy bear markets don’t last forever. Prices may not quickly recover, but the pain of the economic adjustment is temporary. Once prices hit the floor, they don’t go any lower.

It beats a bear market, but returns have been pretty lackluster for both stocks and fixed income. Weakness in the energy sector is masking strength in the rest of the economy. It appears that 2015 returns are going to be lower than average. Looking towards 2016, earnings are expected to grow eleven percent. A return of 10-15% over the next year seems realistic. The most important driver of future returns is the strength of the global economy, which continues to slowly accelerate in spite of ongoing uncertainty. The first interest rate increase in almost ten years would affirm the belief that the economy continues to gain strength.