The Rodney Dangerfield Bull Market

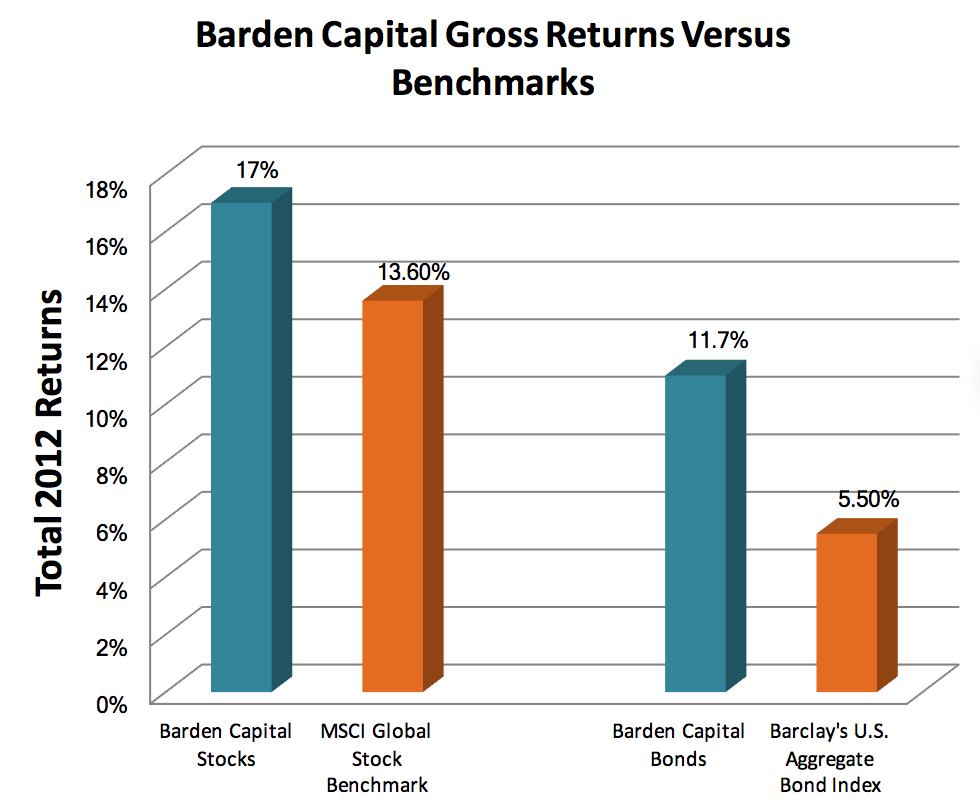

2012 was the fourth straight year of gains for the U.S. stock market. In clients’ portfolios, Barden Capital’s stock allocations returned more than 17%, easily beating the performance of the Global stock benchmark (MSCI Global) which was up 13.6%. Barden Capital’s bond strategies, which were up more than 11%, also outperformed the bond benchmark (Barclay’s U.S. Aggregate) which was up 5.5%.

Since the low for the market in 2009 the S&P 500 is up 122% excluding dividends. At 1,481 the S&P is in the neighborhood of the levels reached in 2000, before the collapse of technology stocks and in 2007, prior to the collapse of the financial sector. As I write this the Dow Jones just closed at a five-year high.

With all of the uncertainty in the world, it’s not surprising that many investors are questioning whether this might be a good time to take some chips off the table. To evaluate the opportunity in stocks we have to compare their expected return to other possible investments.

“Safe Money” Strategies May Not be So Safe

CDs and bonds are pretty straight-forward. Assuming the bank or the bond issuer does not default, the expected return is the interest paid over the life of the bond or CD. Today, you’re not going to find many one-year CDs that pay more than 1%. To put this in perspective, a one year CD holder can expect to double his money in about 70 years. This is an especially unappealing prospect when you consider that with inflation currently running at about 2% a year, in 70 years, you’ll need about $4 to buy one item off of McDonald’s dollar menu.

If an investor buys a long-term U.S. government bond today and holds it to maturity, the investor will earn about 3% a year on his bond investment. This implies that the initial investment will double in about twenty-four years. This doesn’t look too bad compared to CDs, unless inflation goes back to the double digit rates of the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, in which case the investor will deeply regret owning 30-year government bonds.

The goal of long-term investors is to increase the purchasing power of their wealth. So, we need to know the likely expected returns for each possible investment. Historically, the return of stocks net of inflation is in line with the earnings yield. At the peak of the tech stock mania in 2000, stocks had an expected return after inflation of only 3%, compared to the 5% return available from stable CDs. But, investors shunned safety as they piled into stocks in record amounts.

In 2009, investors were stampeding out of stocks. The timing of the average investor was again uncannily bad as they sold when the expected return on stocks approached 10% a year and fled to bonds and CDs when the average rate on CDs dipped to 1%. Today, at record low interest rates and after a 120% rally in stocks, investors are still more likely to be buying bonds than stocks. Stocks get cheap when investors’ confidence is lacking. And it’s no surprise that confidence is shaken after the last few years.

Europe

Going into 2012, the biggest investor fears concerned the breakup of the Euro and the ability of U.S. politicians to effectively govern. Investors assumed that Europe had passed the point of no return. A chorus of highly respected economists including Nouriel Roubini, Nobel laureates Paul Krugman and Joseph Stiglitz, PIMCO CEO Mohamed El- Erian, and Harvard economists Kenneth Rogoff and Martin Feldstein proclaimed that a Greek exit from the Euro was inevitable. The economists underestimated the willingness of Europe to preserve its unification project which began more than fifty years ago. My sense was that this belief discounted the pride and intensity with which the European leaders were committed to the European unification project.

Barden Capital steadily increased our clients’ allocation to European companies like Budweiser Inbev, Henkel and ASML. These companies serve global markets including the U.S. Some of these companies have greater exposure to the recovering U.S. economy than U.S. multinationals like Colgate or McDonalds. The fact that these companies are based in Europe caused investors to discount them severely, to the point that many of them were trading at valuations only half as great as their U.S. based peers. The successful trade was to bet against the doomsday consensus. European stocks outperformed the U.S., and Greek bonds are up 78% from January 2012.

Last fall I attended the European CFA Institute conference in Prague. My intention was to learn which force was stronger, the force of integration, or disintegration. I had the opportunity to see firsthand the commitment with which Europeans approached their unification. Like any emerging economy, Europe will hit its share of potholes. Like the old cliché, that which doesn’t kill them makes them stronger. Their successful navigation of this crisis is tightening the bonds of the European Union.

Debt Ceiling and the Fiscal Cliff

Politicians continue to exert their influence on the psychology of investors. They avoided substantial tax increases after a late night vote after the first of the year. Now, it seems that they will avoid a last minute vote to increase the debt ceiling, avoiding a repeat of the 2011 showdown.

Many are rightfully concerned that the long-term debt of the U.S. government requires a rigorous evaluation of the government’s top spending priorities. But, throughout all of the sound and fury surrounding the debt outlook, interest rates have remained near generational lows. It seems that overall interest rates are not just driven by the level of the government debt, but by the overall level of debt in the economy.

Since the credit crisis of 2008, most of the U.S. economy is reducing its debt levels. The federal government represents about 25% of the economy. The other 75% of the economy is driven by state and local governments, the private sector and the corporate sector. These sectors have worked to aggressively reduce their debt loads. The private sector debt load is lower today than it has been in twenty years. Banks and non-financial corporations carry lower debt levels than at any other time in recorded history. State and local governments have been cutting spending and laying off government employees at an unprecedented pace. The aggressive deleveraging of 75% of the economy is more than offsetting the federal government’s increase in debt.

Throughout all of the uncertainty, the stock market continues to appreciate as corporate earnings increase. The lesson for investors over the last fifteen years is that the booms are never as permanent as they seem, and the busts aren’t irreparable. Capitalism and free markets consistently adapt and evolve. Yet, investors have always tended towards extremes in sentiment. Throughout the history of markets, they invariably buy when it appears that nothing can go wrong, and they sell when it seems that nothing can go right.

Today, most investors still see the glass as much less than half-full. With CDs paying around 1%, safety is very expensive while owning a share of current and future corporate earnings is historically cheap. As Warren Buffet suggested, we will continue to be fearful when others are greedy, and be greedy when others are fearful.